Keys To Success

For students across the country attending universities with Jewish populations large and small, the extent of flexibility of the residence life staff, when matched with a student’s sense of commitment, can make the biggest impact on maintaining a frum lifestyle on campus.

This is not to underestimate the challenges faced by observant students, who may face everything from loud music on Friday night to non-kosher roommates who borrow kosher cutlery to flat-out discrimination because of practices, beliefs or appearance.

Rabbi Hart Levine, founder of Heart to Heart, a college program that organizes friendly Shabbat meals, faced many adversarial situations at the University of Pennsylvania.

“I had a roommate who was Jewish by birth alone, and it was challenging to create a really vibrant Jewish space in our room,” said Levine, who said the roommate was once offended at an assumption that he would attend services on Yom Kippur. “It created some tension.”

Most residence halls have multiple layers of security, to students’ benefit. The first entry into most buildings for most campuses is the swipe of an ID card. Identification cards are calibrated in order to serve several functions on campus, one of which is to permit entry for students into only their residence. For shomer Shabbat students, this can be an obstacle or hindrance to maintaining observance while living on campus.

The swipe of an ID is standard, but most campuses, especially those familiar with the needs of Orthodox students, can and do provide manual keys that can be used on Shabbat. In Saritte Perlman’s case, because Guelph University in Ontario is unaccustomed to the needs of Orthodox Jews, the outside door key can only be opened with a universal key, something the university was unable to provide to a student. On Shabbat, Saritte either lingered outside the heavily trafficked front door waiting for someone else to enter, or knocked for a resident assistant to let her into the building.

“At first it was awkward standing around,” she said. “But soon people started to recognize me and resident assistants would come to expect me on Fridays and Saturdays.”

At New York University, by contrast, Gabrielle Lasher faced the typical ease with which Orthodox students are accommodated at more heavily Jewish institutions. She had a manual key and showed security her identification, without swiping it. Lasher said that most of the security officers on campus had no issue with the special arrangements that Orthodox students made.

For a school like Princeton, which recently built an eruv, the challenge to keeping Shabbat before was clear. Not only is it necessary to have keys to the outside doors, but without an eruv it was also impossible to carry them or keep them in pockets, according to halachah. While the university was working on building the eruv, the office of residence life made it as easy as possible for religious students to carry their keys on campus.

Rebecca Dresner, a senior at Princeton, told OU-JLIC, “At orientation male students are given Shabbat belts and female students are given bracelets to carry their keys. The belts and bracelets don’t cost a lot and what we pay is a deposit — it was $10, if that. If we return the bracelets and the belts, the fee is returned at the end of the year.”

While any student could purchase a Shabbat belt or bracelet themselves, the fact that Princeton provided them made it clear to Dresner from Day 1 on campus that the school was aware of and sensitive to the needs of Orthodox students.

High-rise residence halls present another unique challenge for shomer Shabbat students, who try to avoid getting placed on the higher floors. Fortunately most school residence halls cap out at around four floors — though at urban schools like NYU, they can be much higher.

For Lasher at NYU, the stairs during her freshman year were a challenge. Despite requesting a lower floor residence hall room, she ended up on the seventh floor. While it was an unexpected workout every Shabbat, Gabrielle would have obviously preferred being on the first three floors with most of her peers. She told OU-JLIC that NYU did its best to accommodate Orthodox students’ requests to live on a low floor, but she was one of the unlucky few who found herself hiking up the stairwells.

Once inside the residence hall, there are often a few potential halachic obstacles to avoid. In stairways and sometimes in bathrooms, motion sensors are an obstacle for Orthodox students. Some universities will agree to deactivate them on Shabbat.

Leah Sarna, a graduate of Yale University, found that the residence life staff went above and beyond to ensure a smooth transition into residence hall living. Before orientation weekend, students have the opportunity to inform Yale that they are Sabbath observant. The university then assigns a member of the maintenance staff to ensure that their needs are met on move-in day, a Friday. This maintenance staff member gives out manual keys and automatically deactivates motion sensors. The rest of the year, this staff member goes around before holidays and on Friday afternoons to deactivate the sensors in every bathroom and stairwell that Orthodox students use. Jewish students on campus grew to form a relationship with this staff member, named Hesh, who Sarna deemed “The Man” in an endearing tone.

While most major universities are accommodating overall of the requests from Orthodox students, few waive the freshman lottery system for roommates.

Gabrielle Lasher at NYU worried that living with a non-Jewish or non-observant Jew would be a stress on both roommates. What if the non-Jew wanted to watch TV or left the bedroom lights on after leaving the room on Friday night? While NYU was once willing to place Orthodox students with one another, the college recently changed that policy. Lasher believed that it was because residence staff wanted to integrate students more across religious lines.

The university did not respond to OU-JLIC’s request for comment about the current policy.

Lasher said she would not have objected to living with a non- Jew, as she wished she had made more friends with students outside of the Jewish community.

“Most of the places [where] we made friends were in our dorms and in the dining halls the first year,” she said. “We were all on the same floors for the most part — the lower floors of certain buildings, because we requested to be there so we didn’t have to climb to higher ones on Shabbat. We all went to the kosher dining hall together, which was separate from the ones that other students went to. While I made some friends in my classes, the Jewish students tended to bunch together in groups because it was easy and the most comfortable.”

In 1997, Yale University was embroiled in a lawsuit with a group of five students (“The Yale Five”) who claimed their religious needs were not accommodated by the school. Campus policy then prohibited the students from living off campus together with other Jews of the same gender, which would have been a contradiction of policy requiring first- and second-year students to live on campus on mixed gender floors.

At the time, the case was a source of tension between the university and Orthodox students, but Sarna insists that she had no issues requesting single-gender bathrooms at Yale, despite living on mixed gender floors. Sarna also found ways to reduce tensions with non-Jewish roommates.

“I really recommend that people buy a KosherLamp (a lamp able to be dimmed on Shabbat) for their side of the room,” she said. “I always remind my roommates to turn the light off on Shabbat and holidays, sometimes with a sticky note next to the switch. As it is people normally watch TV shows on their computers or in the common room, so my roommate watching stuff on Shabbat isn’t ever a problem, we don’t have a TV in our room.”

Other students said that there were few adjustments that needed to be made with non-Jewish roommates, as there were no kitchen and kashrut questions in the equation.

David Barkey, an expert on religious freedom for the Anti-Defamation League, said great progress has been made in residence life housing on campuses across the United States.

“The issues we have on campus are less about religious accommodation and more issues pertaining to anti-Israel professors that have a clear anti-Israel bias,” Barkey said. “Nothing has come across my desk where there was a school that was refusing to accommodate.”

Rabbi Hart Levine urges those who encounter compatibility issues with roommates, residence hall neighbors or others, particularly if they are non-observant Jews, to keep things civil and not give up on the ability to reach compromises.

“I had a roommate who played music on Shabbat, but when we asked him not to when we had Shabbat dinner in the room he was totally OK with that,” Levine said. “We often invited him to join us. Open communication along the way can be the most important asset.”

By Bethany Mandel

Advocating for Shabbat and Chag Accessibility for Religious University Students

Missing classes/exams/graduation for holidays or Shabbat

Jewish holidays often fall during the week, and since Jewish law precludes writing or working on those days, it makes it hard to attend class. Furthermore, the prohibition against writing is incompatible with taking exams (save for perhaps oral exams). Besides for the technical and legal difficulties that arise, it also is not considered the “spirit of the law” to celebrate or commemorate Judaism’s holiest days by going to class. It has become rare for classes to meet over Shabbat but if so, that would also be an issue. There’s also the issue of graduation, which sometimes comes into direct conflict with either Shabbat or Shavuot, and which makes it difficult for religious students and their families to attend.

Missing social events and other optional events in favor of religious celebrations is one’s choice, but when it comes into conflict with something educational and mandatory, students should not have to make that decision. If Universities value diversity, freedom of religion, and all students’ full participation in their University experience, they should do whatever they can to alleviate or solve such conflicts. Additionally, if universities want to prove themselves as attractive destination for talented observant students, they need to show themselves willing to accommodate them. And finally, but not least, there is the “Free Exercise Clause” of the First Amendment, which prohibits actions that would prevent individuals from observing their religious practices, which applies in many situations with public colleges, and sometimes with private colleges. (This legal clause is relevant to most of the situations in this document.)

Many universities (public & private, e.g. Michigan, UMass, Berkeley, Penn, Cornell) and even some states (e.g. NY, MA) have official policies and specific procedures in place to work around or through conflicts. This usually entails not penalizing students for religiously-mandated absences – and either alternative or rescheduled opportunities to make up the work. Students often have to bring scheduling conflicts to the professor in the first few days of class (or when informed of exam dates), and work out a reasonable plan with them. They also sometimes have to bring a letter (usually from a rabbi or chaplain; Hillel or Chabad staff can usually write one) to prove that they are observant and/or that attending class or exams would not be possible for religious reasons. Professors might also ask for an official list of Holidays – specifically those on which work is forbidden – which can be found in some of the above links.

If professors are uncooperative or antagonistic, students should think about contacting the Department Chair, Dean of the School, Ombudsperson, or Provost, in consultation with a rabbi, chaplain, or religious staff member.

Eruv

Building an eruv is a lengthy and complicated process, that includes the university but also relates and extends to the local city and entire Jewish community. It usually takes a few years, over $20,000, knowledgeable rabbis, and a host of dedicated volunteers. It is especially important for attracting young couples with children (which includes many grad students) and long term community growth, and for allowing and promoting students to have communal and community-friendly potluck meals and picnics. Permission and permits usually need to be obtained from: electric/phone company (if using their poles), municipality, and any buildings utilized for the eruv.

The university’s assistance could be used to assist in:

- Funding eruv construction

- Obtaining permits from local public and private companies

- Allowing access to and usage of university property for eruv construction.

Lighting Candles

Shabbat / Yom Tov

You’re supposed to light where you eat, unless you eat in a communal area, in which case lighting in your specific room would be preferable. But “chamura sakanta mei-issura” – in cases of safety concerns, safety overrides halachik preferences – so if lighting in your rooms is unsafe, better to light where you’re eating Shabbat dinner. If your only option is lighting in your room, you can use incandescent lightbulbs, or light on tin foil in a metal sink surrounded by water (or some other fire-safe way)

Chanukah Candles

One is supposed to light in one’s home, in the place that one sleeps — not in any other public place that is not one’s home. Some people light outside the doorpost of one’s home, but usually (in America) indoors. Practically, some options of lighting locations in a dorm are:

- Outside of one’s doorway

- In the lobby by the exit (assuming it’s your exit)

- By a window that faces the public view

- Inside your room by the door on the right side, opposite from the mezuzah

- Worst case scenario, one can light on an inner table in one’s common room

If dorms have a policy against candle lighting in rooms, suggest setting up a table to be set up in the lobby, where it can be under the supervision by security guard (and fire marshall?)

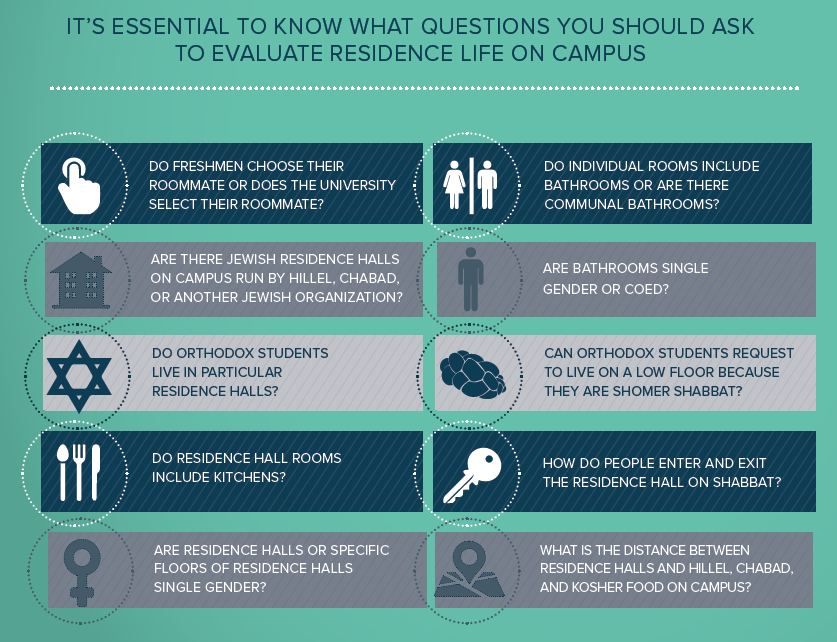

Dorm Access for Shabbat Observers

Shabbat is among the foundational beliefs and practices of Judaism. It is a day of rest, of ritual, and of community, and many religious laws were set up around the day – including the prohibition to use electricity. Debated as to whether the prohibition is Biblical in nature or Rabbinic, there is no question that it is forbidden for Shabbat-observing Jews to use electricity or electronic appliances on Shabbat (barring life-threatening situations). For those who observe its rules, inserting electronic keys or using electronic keypads is thus undeniably forbidden on Shabbat, which precludes usage of and access to such rooms.

In recent years, many universities have begun introducing electronic access to dorm rooms and building, usually by way of key card access. This proved to be an issue for Shabbat-observant students, who make up an important and growing demographic and are key contributing members of the university community. To solve this issue, many schools (including Brandeis, Cornell, Harvard, Maryland, Michigan, UChicago, Yale) have gone out of their way to provide manual keys to accommodate Shabbat-observant Jews, while others (including Brown, Columbia, Penn, Princeton) chose to keep some or all buildings under manual access, or design alternative routes for building access.

Because access to one’s building and room is not a perk but rather a necessity, solving this question is of prime importance and imperativeness – and falls under the requirement of fairly accommodating students’ religious needs. Safety is also of paramount importance, so leaving doors open or not granting access to students and requiring them to wait around for someone to open their doors are unsafe, unwise, and thus not viable options. Another possibility is asking someone who not of the Jewish faith to use electricity on their behalf, but that practice is questionable from a Jewish legal perspective and not intended as a long-term solution. Logistically as well, this would not be an efficient or reliable solution, plus it could create an uncomfortable dynamic for those assigned to escort and do the observant Jews’ bidding.

Possible solutions do include:

- Providing manual keys for students who request them – and if that is not available, then installing manual locks on the rooms of those students. Some universities charge a fee (~$50) for the keys, which may or may not be refundable upon return of the keys at the end of the year.

- Leaving specific room, floors, or dorms with non-electronic access, and setting them as preferred it guaranteed housing options for Sabbath-observant students.

- Setting up procedures and policies for non-electronic access to buildings, such as going around the security desk using Sabbath identification lists or other security measures (this is only relevant for building access).

By Rabbi Hart Levine